It is now Anno Domini 2025, and for some reason, people keep trusting email. That needs to stop. Let’s talk about why–but first, let’s talk about why I’m telling you this now.

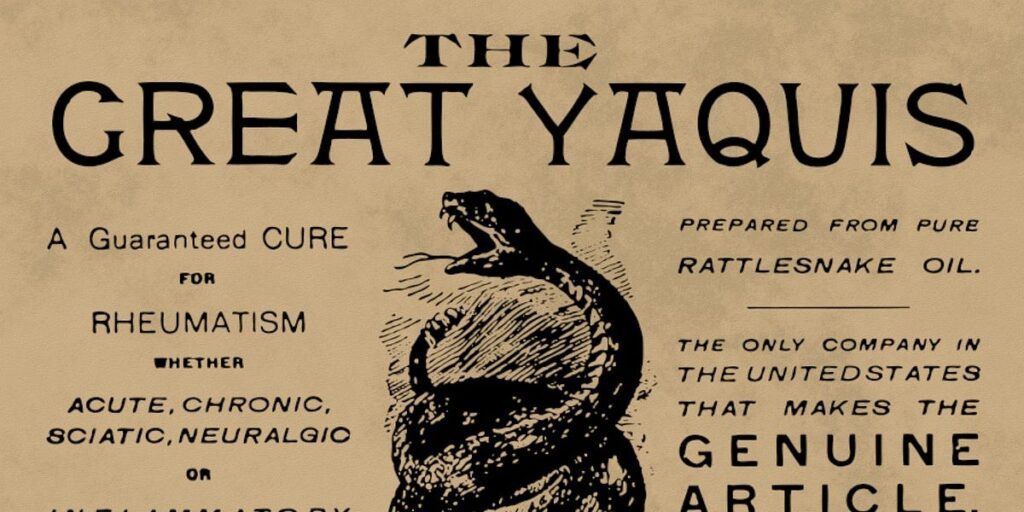

All things happen in cycles, including grifting. And folks, we are at an absolute peak of griftitude right now, similar to the days of snake oil peddlers traveling town to town and selling bottled garbage from the back of a wagon.

One type of fraud that’s peaking right now is payroll/escrow fraud, and it depends very much on people trusting email for things they shouldn’t. It’s an easy grift with a decent success rate and potentially massive payoffs.

Anatomy of an email-based grift

First, you discover an existing payer/payee relationship. This is usually public information and not all that hard to figure out. For example, you might discover that Architect A won a public bid for a construction project. That project will usually have publicly disclosed target dates for completion of various stages as well as the project as a whole–if a stage is nearing completion, this is a potential target, so you do a little more research.

Next, you discover that Architect A is using electrical vendor B to handle the lighting. Typically, the architectural firm gets paid first, and subs out the rest of the contractors. So now, you want to figure out who the accounts payable and receivable folks are at both A and B–again, usually publicly accessible information, not hard to figure out.

Now, you’d like to actually compromise somebody at either A or B, and both if possible. If you can manage it, your odds get a lot better, and you might be able to figure out a way to score bigger and possibly multiple payoffs. But it’s not strictly necessary. Let’s say you were not able to get into the actual email of anybody at either firm–you’re still in the ball game, no worries.

Next step, you know that the lighting for the project is done, and you know who accounts receivable at electrical engineer B is, and who the accounts payable at architect A is. So, you spoof some email from B to A. First, you say that B’s banking information has changed–and you “correct” it to a short-lived account you’re using for the grift.

If you timed it right–and if the accounts payable person at A is a useful idiot–the payment for engineering firm B winds up in your own account, and you immediately move the funds out of that account to someplace offshore and crime-friendly. If it takes more than 48 hours for A and/or B to figure out the money went to the wrong place, you’re home free–they can’t get the funds back, once they’ve moved offshore.

This doesn’t need to be an architect and an engineering sub–another common example is real estate firms and closing attorneys. Real estate sales are also publicly posted data, and you can impersonate a real estate firm and ask the closing attorney to wire the escrow (money put down prior to a purchase completing) to a different bank account. It’s the same grift, with the same potentially enormous one-time payout.

The same technique works for payroll

For construction projects, this can be a single score worth potentially millions of dollars. But what if you got some intel on a business that isn’t a construction, architectural, or real estate related business?

No problem–you’ll need to downshift and look for a smaller payout, but payroll fraud works the same way and requires even less research.

All you need for this one is to know who handles the payroll for a business, and who grants bonuses in a business. Now you impersonate the person authorized to grant bonuses, email the payroll person, and authorize a bonus–usually between $3,000 and $10,000–to one or more employees.

Since you already impersonated those employees and changed their ACH target the day before, those several-thousand dollar “bonuses” go to you, not the employees… who weren’t expecting a bonus, and therefore don’t get alerted by it not showing up.

Generally speaking, you target this one in between paydays, because an individual employee who doesn’t get a paycheck they’re expecting will ring the alarm fast.

Impersonation is incredibly easy

It’s tempting to think this is super high tech information security stuff, but it’s anything but–because email was never designed as a secure protocol in the first place.

Let’s look at physical, postal mail first. What happens if you write “President of the United States of America, 1600 Pennsylvania Ave, Washington DC 20500” in the upper left corner of the envelope?

Your letter gets delivered, is what happens. The postal office does not attempt to verify the “return address” in any way whatsoever–it’s not a form of authentication. It’s on you to realize that this dinky little envelope with a kitten stamp and a postmark from Slapout, AL did not actually originate in the Oval Office.

Email works the same way! Anybody can write anything they like in the FROM: section of an email. It is not validated, in any way, period. If you blindly trust an email based on the FROM: you are making the same mistake as somebody who blindly trusts a postal letter based on what’s scrawled in the upper left corner of the envelope.

Infiltration isn’t that much harder

So far, we’ve talked about how grifters can separate fools from thousands or millions of dollars with nothing but publicly available information–and that is, by far, the most common form of grift in my experience as a very senior IT person.

An advanced attacker might aim a little further north, though, and try to genuinely compromise a target’s email account. If the attacker can gain control of a target’s email account, the attacker can now gain access to private information which makes that crucial attack scheduling far more accurate.

In our first example, we were banking that electrical firm B will have completed the lighting phase of the project on the stated date when the building plans were first announced. If that date slipped badly–or, wonder of wonders, the firm finished early–the critical email to change the ACH target might arrive too early (and be discovered) or too late (and the payment was already made).

But if the attacker can actually compromise the accounts receivable person–or a C-level–at electrical firm B, the attacker can just monitor that email and wait to act until the exact right time. The attempt is also more likely to succeed because even a paranoid IT expert can verify that the email came from the legitimate account of the target–but the improvement in timing the attack is frankly far more important than the improvement in “legitimacy” of the attack itself.

How can I verify that an email is legitimate?

If you’re expecting a bunch of highly technical stuff about email headers, I’m going to disappoint you–because the correct answer is “you can’t.”

Yes, a sufficiently cautious and well-informed person can first force their mail client to display the normally-hidden message headers, then verify each step the message has taken across the internet. (This is the electronic version of reading all the postmarks on a physical envelope.)

However, the vast majority of targets are neither sufficiently cautious nor sufficiently well-informed, nor will they ever be. And more importantly, while this sort of sleuthery might be accurate enough to tell you whether a message came from a particular server, it can’t tell you anything about whether the message originated with the human it should have.

So the real answer here is, when money is on the line, don’t trust email. If you get an email asking you to move a significant amount of money, or to give someone access to an account (banking, telephone, online gaming, email, or anything else) you’d be upset at losing control over, don’t do it–instead, call that person, ask to speak to an actual human, and verify the legitimacy of the request.

And, this is important… don’t use the contents of the email to contact that person or organization. If you don’t already know their phone number, website address, etc–close the email, look the contact information up from scratch, then contact them that way to inquire about the validity of the message you received.

How do I protect myself from being scammed?

We’ve already covered “you shouldn’t trust email,” so we won’t belabor that point… but we will now point out that you need to make sure that the other people you associate with aren’t trusting “your” emails either.

If you’re responsible for the movement of significant amounts of money on a regular basis, check the policies of the people and the firms who you expect to pay or to be paid. Make sure they know–preferably, in writing–that you will not act on unverified email instructions, and that you will not issue unverified email instructions either.

This is important, because an entity that screws up and sends your money somewhere else based on an email “from” you will frequently try to make it your problem. As far as they’re concerned, they sent that $10,000 somewhere, so they “paid” and if you didn’t get it, well “that’s on you.”

You might be thinking “well, that’s obviously stupid.” Sure, sometimes it’s obviously stupid. Other times, it’s obviously dishonest. Either way, if you don’t have a written policy statement on file that you will not be held responsible for actions taken on unverified email, you might be left on the hook–and court actions will typically cost more than the amount of money in play, so you don’t want to rely on litigation as a solution here.